Aruna, a native of Nagorno-Karabakh with an Indian name: "Do not lose hope; despair is a bad friend."

— My name, Aruna, comes from an old Indian film titled "Forgive me, Aruna." My parents were fans of the leading actress.

— And does your life story resemble Aruna’s from the film?

— Not at all! She's a rich girl on the silver screen who falls for a poor boy, and they live happily ever after. Classic Bollywood film, Aruna replies with a smile.

She was four months into her pregnancy when the child's father left, and now she is raising the son alone.

Aruna Poghosyan was born in the village of Kyuratagh in Nagorno-Karabakh. She received her education in Stepanakert and later taught history and geography in Haykavan village, located in the Hadrut Province.

"Haykavan was isolated from the outside world. The students lacked any understanding of geography, and the maps were neglected, left rolled up, and discarded in a corner. I began teaching the same geography basics to 10th, 5th, and 6th grade students. Just as the students began to grasp the lessons, the war broke out, and we were all forced to leave the village," Aruna recalls.

On the morning of September 27, 2020, they heard explosions and sought refuge in the nearby forest.

"We were a group of about ten families, each with six or seven children," Aruna says. "All we could do was wait in the forest for a car to show up, the children growing hungrier by the minute. Then, one of the young girls spoke up, saying, 'I'm not scared of the shooting. I baked lavash yesterday; I'll go back to the village and get it.' And she did! She ran back and returned with the lavash."

They spent a day in the forest before heading to the village of Mets Tagher with her son and parents, seeking safety. However, even there, they found themselves in the line of fire. “It felt like the war was chasing us. Left with no other choice, we made our way to Armenia.”

Someone she knew from the Kotchor district of Hrazdan offered her a temporary, rent-free apartment. Aruna hoped to return to Nagorno-Karabakh once peace prevailed.

"Nobody had lived in this apartment for a long time. I cleaned it up, and we moved in. The next day, the kitchen was overflowing! Food and essentials everywhere. People kept arriving. 'I'm your neighbor from next door,' one said. 'I live downstairs,' another added. They all reassured me, saying, 'Don't worry, we're here for you,'" Aruna recounts with a trembling voice.

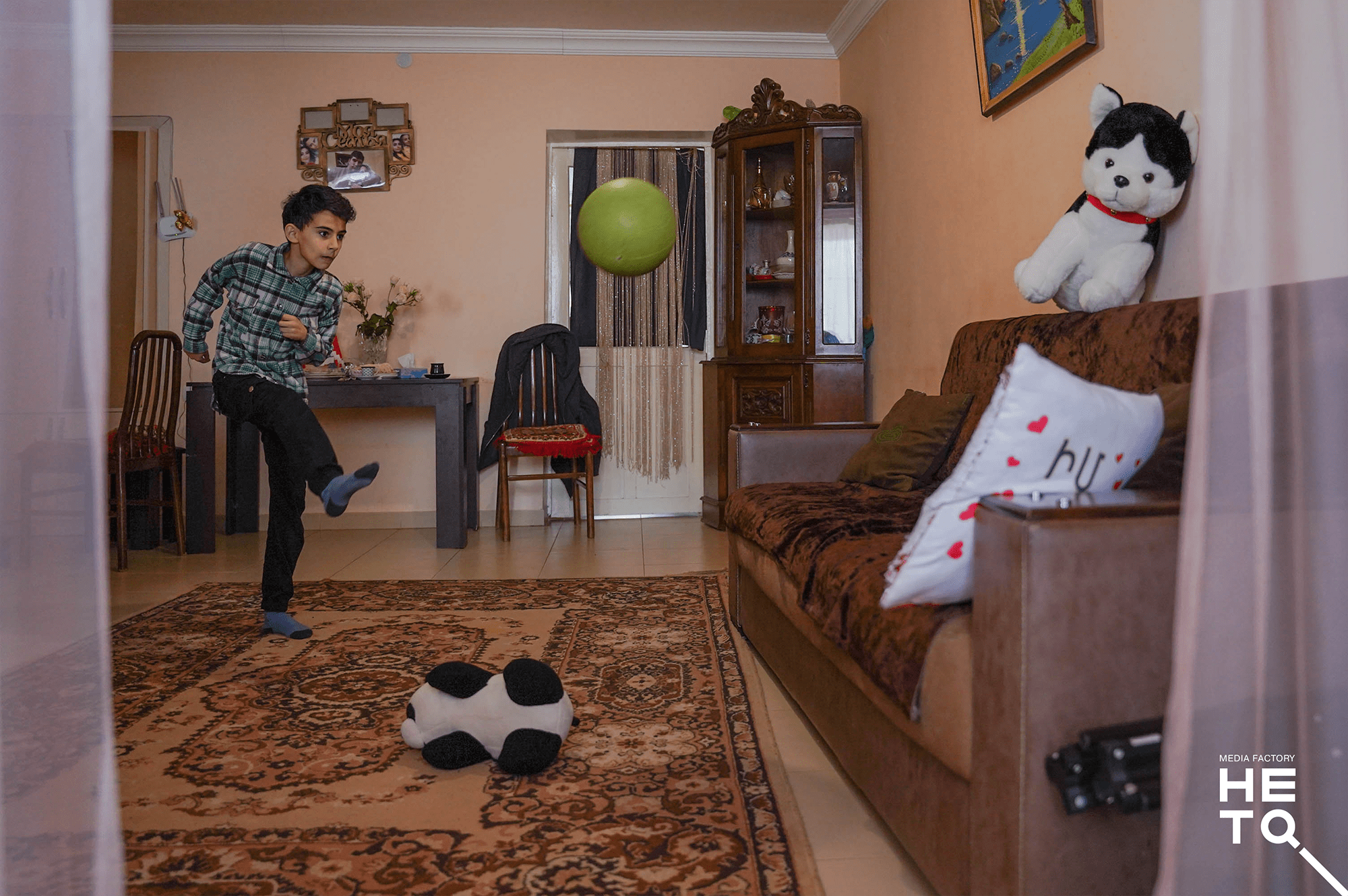

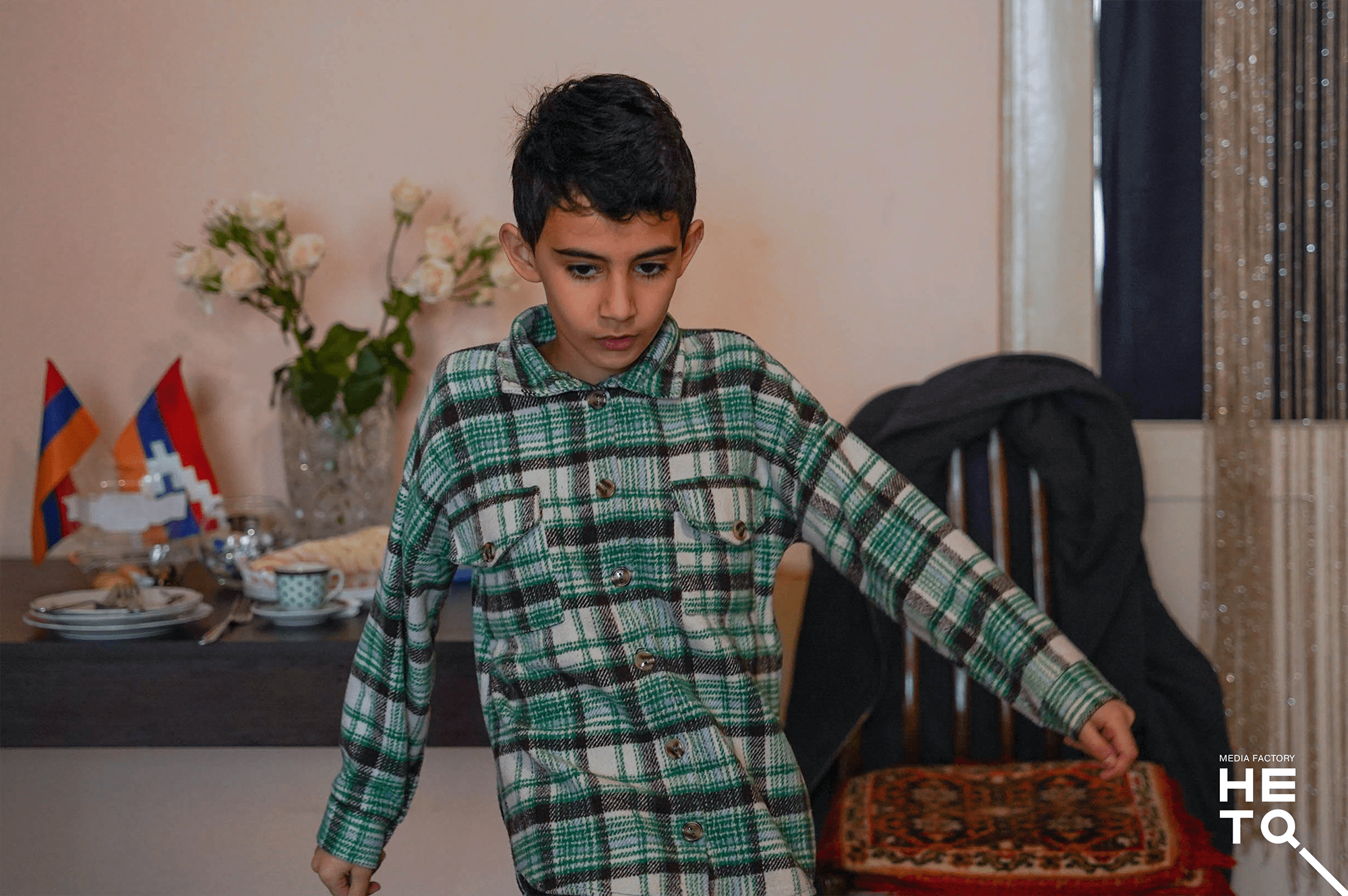

The neighbor was the one who enrolled Marat in first grade. She insisted, "We shouldn't wait for the war to end; the child needs to go to school." Now, Marat is already in fourth grade.

After the war in 2020, Kyuratagh and Haykavan came under the control of Azerbaijan. Aruna and her son settled in Hrazdan.

When talking about Haykavan, Aruna often remembers their dog, left behind, hoping to return one day. She has still preserved the shoes she and her son wore when they came from Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia.

Mother and son communicate in the Hadrut dialect at home.

Aruna couldn't find a job in Hrazdan despite applying to various institutions such as the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports, as well as the Provincial administration. However, in June 2021, she came across an online announcement by the "Resource Center for Women’s Empowerment" NGO offering a free two-month embroidery and sewing course and decided to apply.

"My father was the Principal of our village school for many years," says Aruna. “Since childhood, I believed that books and science were my path. Embroidery and threads – they were foreign to me. I didn't even know how to sew on a button.”

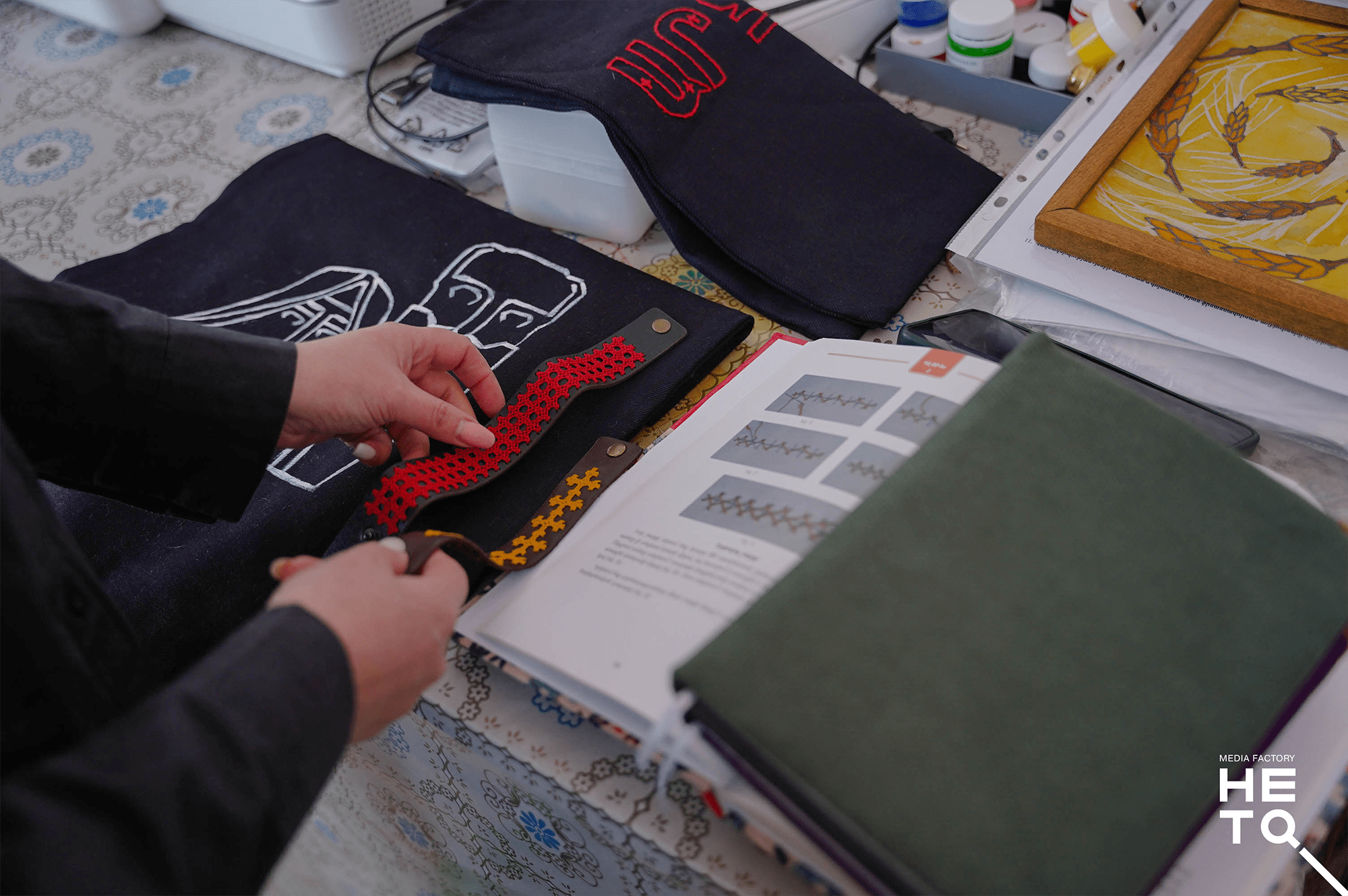

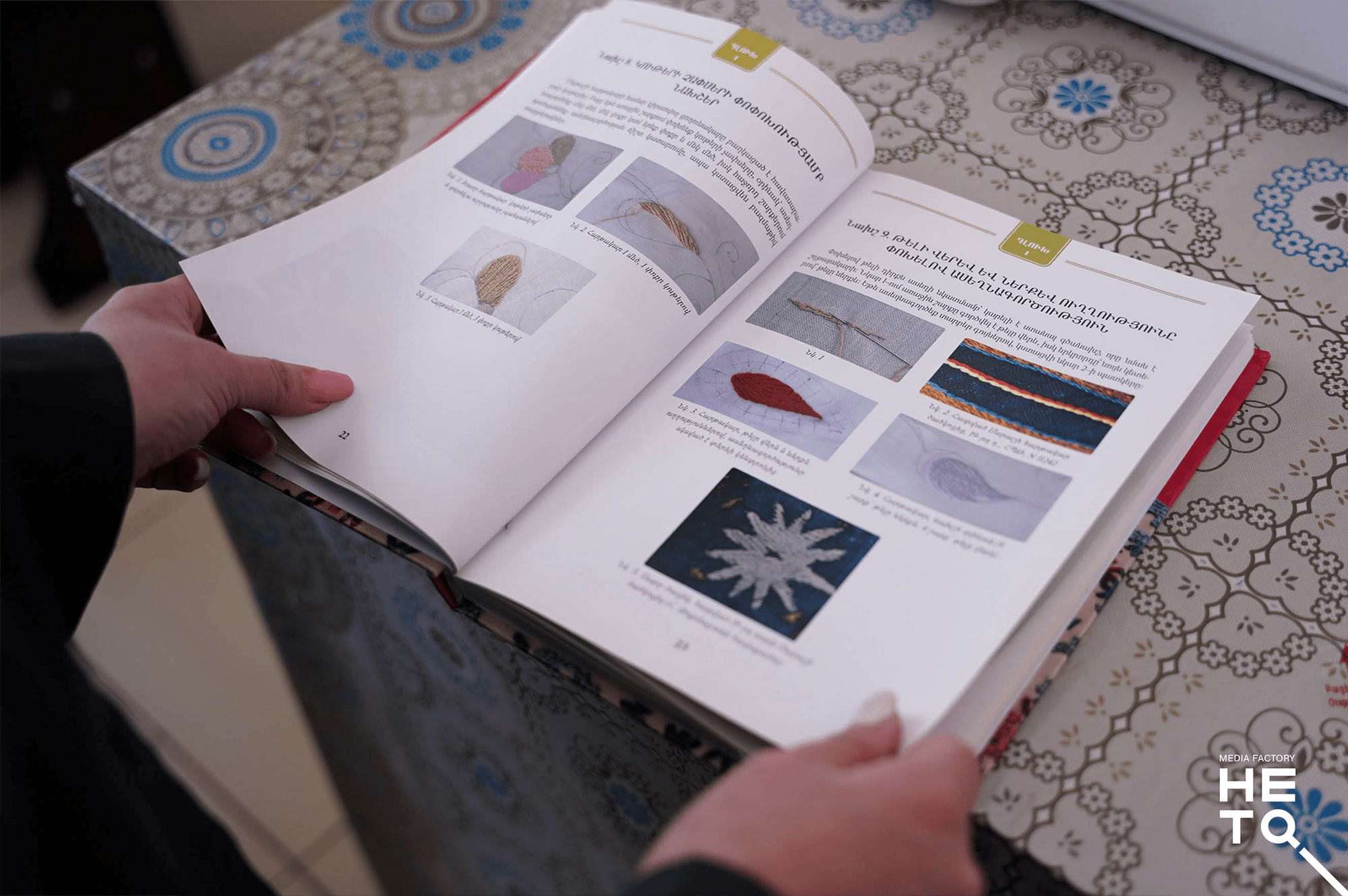

Aruna faced initial difficulties while learning Marash embroidery at the center. Separating the threads, threading the needle quickly, and embroidering patterns were all challenging tasks. "While everyone else was threading their needles, I struggled to do it myself," she recalls. “One day, my son commented, 'Mom, you're falling behind.' His remark served as a wake-up call for me, prompting me to invest more effort, and eventually, I succeeded.”

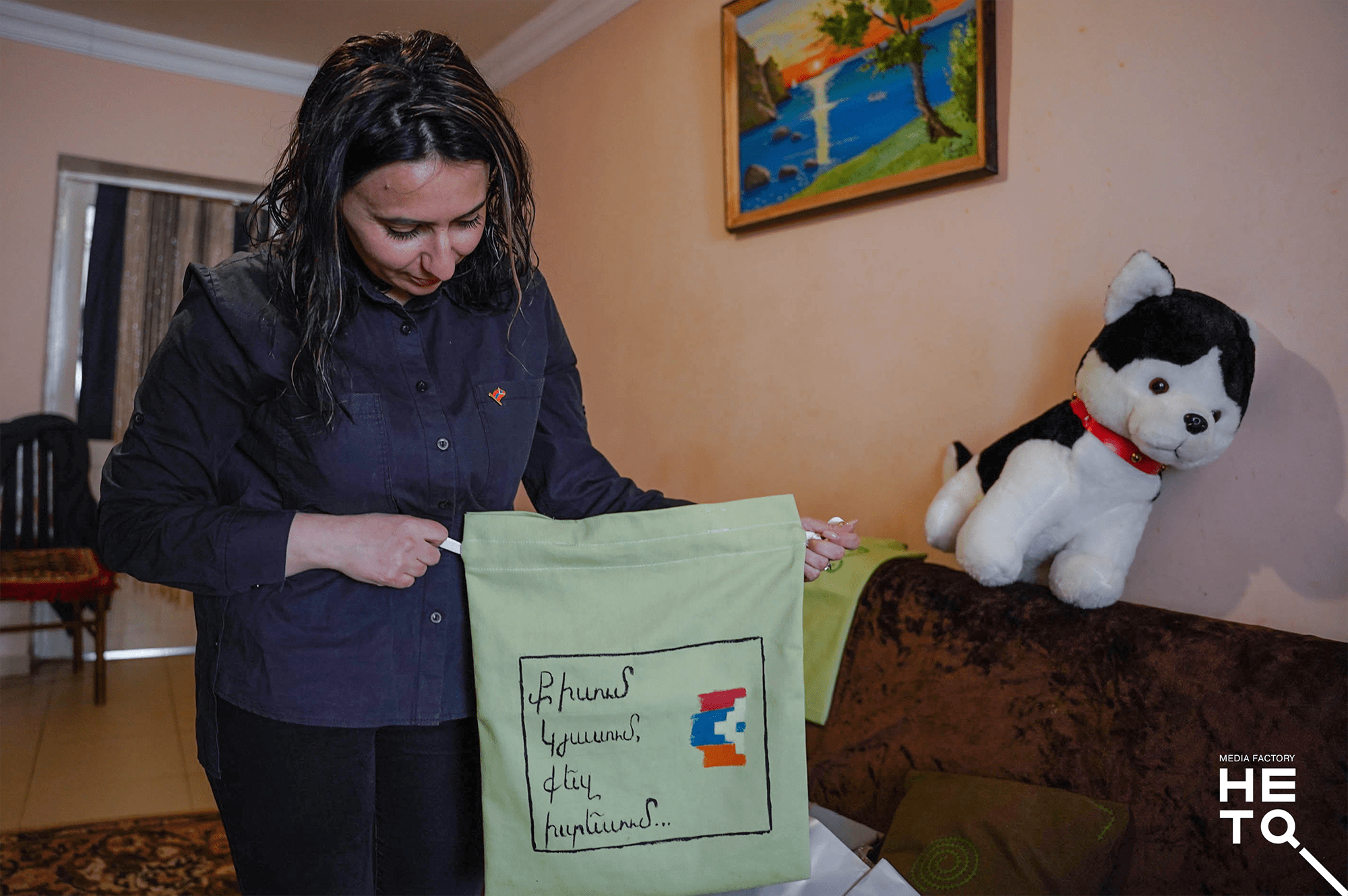

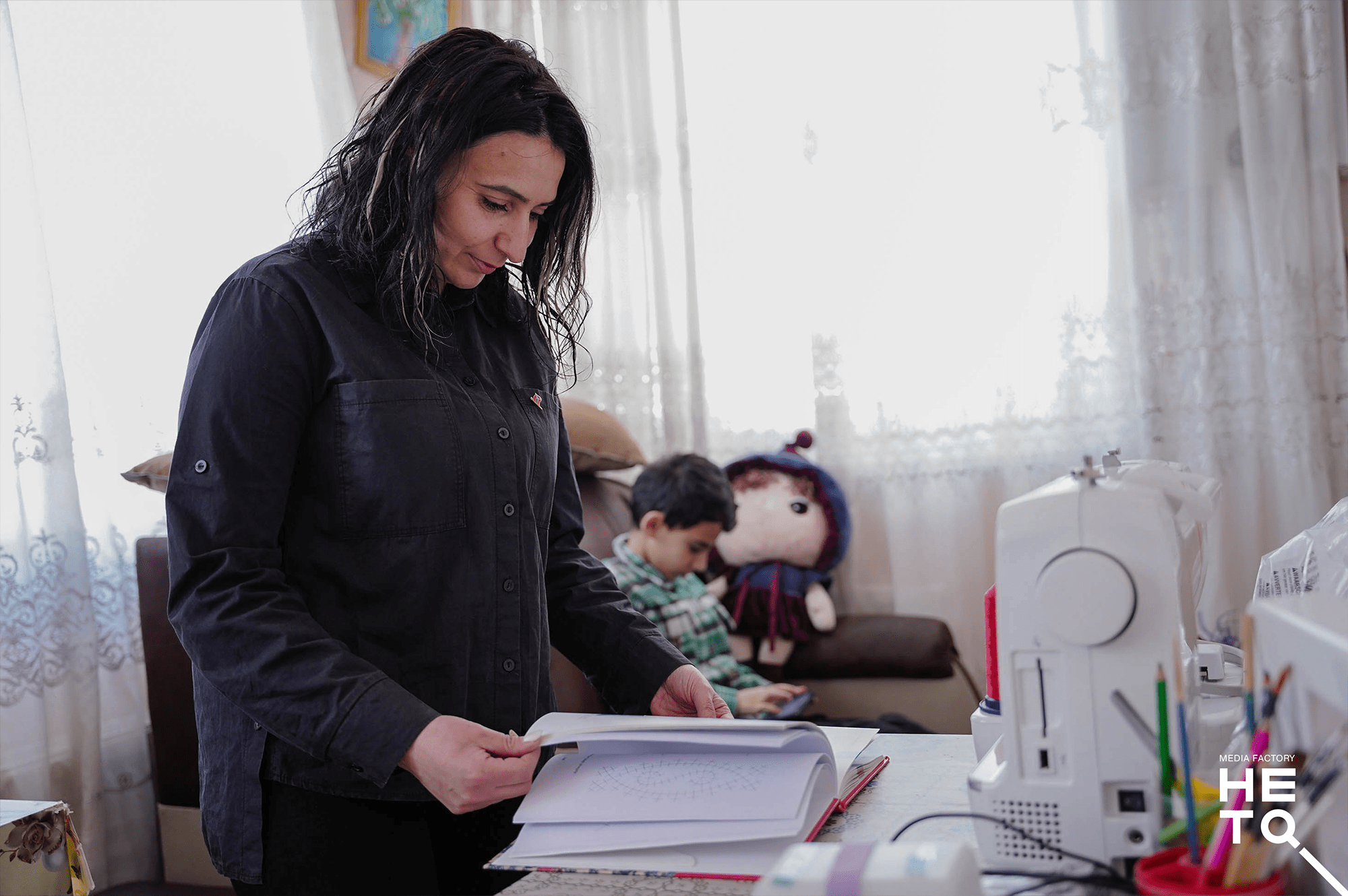

Aruna also attended a sewing course and, upon completion, submitted a business proposal. As a result, the International Organization for Migration awarded her a sewing machine. She now sews, embroiders, and paints, incorporating Armenian patterns and elements of the Nagorno-Karabakh dialect into her work, which includes bedding, tablecloths, notebooks, and clothing.

“Embroidery may not appear challenging at first glance, but it requires simultaneous coordination of hands and mind. Creating fine work demands precise calculation, concentration, and skilled hands. It's essential to remember the starting point and have a clear direction. Through Marash embroidery, I feel like I embrace and pass on a part of our culture.”

The balcony of Aruna's rented apartment in Hrazdan serves as her workspace. The walls are adorned with pictures, and the space is filled with fabric and packaged orders.

Aruna collaborates with the Resource Center for Women’s Empowerment NGO and fulfills local orders. She says this work has significantly boosted her self-confidence.

“Whenever the threads become tangled, I see it as a reflection of life's challenges; some things are easy, while others are difficult. Overcoming these challenges requires patience and hard work.”

Aruna has also been trained in manicure techniques and offers services from her home. In addition to her proficiency in needlework and sewing, she works as a florist-seller at a flower shop.

Having received support in the past, Aruna now extends a helping hand to others. She shares her embroidery skills by offering free lessons to girls displaced from Nagorno-Karabakh in 2023.

“Though it's challenging, I make every effort to stay optimistic and inspire hope in others. I encourage my relatives, sisters, and parents who have arrived from Nagorno-Karabakh not to lose hope, as despair is a bad friend.”

This content was created with the support of the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the United Nations Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF), and the US Embassy in Armenia. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the UNFPA, CERF, and the US Embassy in Armenia.

Authors

Students

Tatevik

Ajamoghlyan

Students

Ani

Balayan

Instructor

Instructors

Mariam

Barseghyan

Team

Team

Harutyun

Mansuryan

Team

Zhanna

Bekiryan

Team

Lilit

Tarkhanyan