The Prescription of Death for the Living: Tracing the Impact of the Unenforced Cadaver Transplantation Law

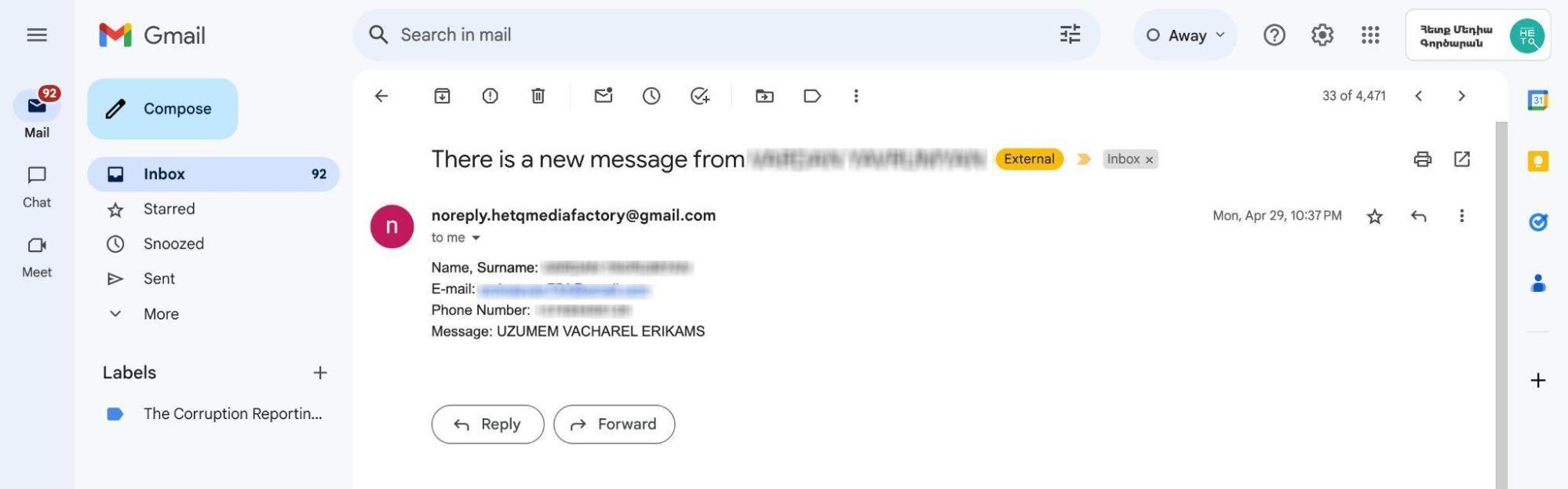

"I want to sell my kidney": Hetq Media Factory received this email in late April while we were still working on this article. When we contacted the sender, a man in his 40s, we learned that he had been trying to find a buyer for his kidney to support his large family for several weeks.

"Once, I saw an announcement on Facebook offering 17 million AMD for a kidney. I reached out, but my blood type didn't match. Years ago, I was also offered $40,000 to sell it in Russia. I agreed at first but then backed out," the man said.

He refused to provide any additional information, even anonymously. He mentioned that he wasn't aware that buying and selling organs was illegal in Armenia and had reached out to us seeking guidance on the matter.

This article is not about the possible buying and selling of human organs in Armenia. We cannot confirm whether such a market exists in our country. However, during our research, we came across various announcements on social media regarding the sale and purchase of organs. If a black market for organs operates in Armenia, the process likely involves the following steps: the buyer and seller connect, undergo necessary medical checks, and, after confirming compatibility, officially document the organ donation as a charitable act. Financial transactions are handled privately, before or after the surgery, outside the hospital.

Our previous article explored organ transplantation in Armenia, raising questions we will try to answer in this piece.

Dialysis has split my life in two

Five years ago, Anahit (name changed at her request — ed.) had to terminate her first pregnancy due to kidney failure. She is still unable to conceive. Now, at 28 years old, her kidneys are shrunken and wrinkled.

"My mother and several relatives were tested as potential donors, but none were compatible. My doctor doesn't seem optimistic about finding a donor here. I might wait another year or two, but if cadaver transplantations aren't allowed in Armenia, I'll consider going to Europe for transplantation," Anahit shared.

She covers most of her medication costs herself. Shortly after her diagnosis, Anahit began dialysis (a procedure that artificially filters the blood when the kidneys are no longer able to remove toxins naturally through urine). This procedure needs to be done three times a week, with each session lasting three hours.

Dialysis has dramatically altered Anahit's life. She explains:

“I go to the hospital at 6 in the morning. Afterward, I feel weak for several hours, unable to stand, and experience pain. Overall, dialysis has split my life in two. I work part-time as a saleswoman; can't manage more than that.”

Anahit knows several young people in her city who have the same illness.

"They are also considering going abroad, but I'm unsure how likely they are to return once they settle there. I don't see much hope for us here in Armenia," Anahit says.

I am asking God for just one kidney

"I am praying to God, asking for just one kidney. I understand that every organ is important to its owner, but please let me live for the sake of my three children," Heghine Mirzoyan gets emotional.

Several relatives offered to donate a kidney to 36-year-old Heghine, but none were compatible. Her illness began four years ago.

"I can't cope with my illness; I feel like I'm falling apart, she says. "I used to work in agriculture, but now I can barely manage household chores.”

Davit, Heghine's 28-year-old brother, began experiencing similar kidney issues after the 44-day war. He's been monitoring his creatinine level regularly for the past eight months. If it exceeds the safe limit, he'll need to start dialysis and will be assigned a disability rating.

Davit is married and has a daughter. He used to work as a truck driver, but now, constant headaches, fainting weakness, and high blood pressure make it impossible for him to work.

"There are times when you have to rely on your brother for help because you can no longer earn a living. Your life and goals completely change, and you feel like you’re only half a person," Davit says.

Cadaver transplantation

A person can become an organ donor even after death. While a living donor can give one of his kidneys, cadaver transplantation allows for the use of all of the deceased's organs. This is a common practice in many countries: when brain death is confirmed, healthy organs become available for transplantation.

Although Armenia has a law permitting cadaver transplantation, it is not currently being implemented.

If cadaver transplantation is implemented in Armenia, the following procedure should be followed:

- A special committee confirms the patient’s brain death.

- The ARMED.am registration system is checked to determine whether the deceased is a registered donor.

- If the person did not object to becoming a donor during his lifetime, consent must be obtained from his next of kin. A designated doctor will discuss this with the family.

- If permission is granted, healthy organs are harvested and, if necessary, transported to the hospital where patients on the waiting list are awaiting transplants.

- The transplantation is then performed.

Brain death is considered the same as human death.

"Brain death is the complete and irreversible loss of all brain functions, occurring while the heart and lungs are maintained by artificial respiration. The death of the brain signifies the death of the individual." This is how the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Armenia defined brain death in 2010. Once brain death is confirmed, cadaver transplantation can be performed to save the lives of others.

Araik Voskanyan, head of the Department of Surgery at Astghik Medical Center, states that the main barrier to implementing cadaver transplantation in Armenia is the lack of public awareness.

"Organs should be harvested from a deceased person while the heart is still beating, but it's important to explain to the public that a beating heart does not mean the person is alive.

After brain death is confirmed, it's crucial to act quickly with the family. Each organ has a specific time window of viability: the liver, for instance, can be kept for up to 12 hours, but it’s best to transplant it within 8 hours. Beyond this period, the liver becomes unusable no matter what preservation method is used. The longer the wait, the less effective the transplantation and the higher the risk of rejection. The system needs to operate precisely and efficiently, like a well-oiled machine”, Araik Voskanyan says.

The law on paper

There are two types of donor consent for cadaver transplantation worldwide: informed and implied. Informed consent requires a person to provide written approval for the use of his organs after death.

Implied consent means that if a person has not expressed a refusal to donate his organs during his lifetime, his organs can be used after his death.

In Armenia, cadaver transplantation was permitted under the second chapter of the 2002 Law "On Transplanting Human Organs and (or) Tissues." This law stipulated that individuals who consented to organ donation during their lifetime could become donors. A 2009 amendment further specified that if a person did not provide written consent or refusal during his lifetime, his organs could still be used for transplantation after his death.

Starting in 2022, a new option for organ donation was introduced, defined by the order of the Ministry of Health. Unless a person explicitly declares in writing that he does not wish to be a donor, he is considered a potential donor after death. However, a family member's consent is still necessary.

Our inquiries to the Ministry of Health did not help to clarify when the cadaver transplantation system will be implemented. The Ministry informed that it would begin once the organ donor registry was operational, but the launch date for the registry is currently unknown.

The procedure for establishing and implementing the organ donor registry was adopted and approved in January 2022 and came into effect in November 2022. The software for the registry, as approved by the order, was assigned to be developed by the "National Electronic Healthcare Operator" CJSC.

Officially, no cadaver transplantations have been carried out in Armenia over the past 22 years.

While Armenia performs kidney, liver, and cornea transplantations, the first two are currently only possible with a living donor. A liver transplantation costs a total of 20 million AMD, of which the state reimburses 5 million AMD, the hospital contributes 3 million AMD, and the patient is responsible for the remaining 12 million AMD. Kidney transplantation costs approximately 7.5 million AMD, including preoperative medical tests, special medications, and surgery. The state reimburses 4 million AMD of this cost.

Corneal transplantations in Armenia are performed using cadaver donor corneas, specifically imported from the USA as needed. Corneal lamellar surgery, excluding the cost of the imported cornea, costs $2,000. However, if only the affected part of the cornea is replaced, rather than the entire cornea, the procedure is three times more expensive.

Ani Hambardzumyan, a resident doctor in the Department of Ocular Inflammatory Diseases at the Ophthalmological Center after S.V. Malayan, says that cadaver corneal transplantation in Armenia would make the procedure more affordable for patients.

“Currently, we have to pay for imported corneas that are preserved with special materials. If we could source them locally, we wouldn't have to pay, as the sale of organs is prohibited in Armenia. While surgeries are generally more affordable here, even when patients are treated under state order, they still have to cover the cost of the cornea themselves. Introducing cadaver transplantation would completely change this situation.”

Slow steps towards introducing cadaver transplantation

Helen Nazaryan, head of the Hemodialysis Department at Arabkir Medical Centre, coordinator of the kidney transplantation team, and consultant for the Ministry of Health, explains that the registry prototype is integrated with ARMMED.AM. Once patient data from all dialysis departments across Armenia are entered electronically (currently, some records are electronic, while others are still paper-based), the registry can be established. This will facilitate the creation of a priority list for transplant recipients, enabling the quick identification of suitable recipients when an organ becomes available.

"The registry includes details such as blood type, diagnosis, hepatitis status, and more. The registry is already being built. In other words, work is being done in that sense. The main challenge in Armenia at the moment is properly organizing the process of harvesting organs from cadaver donors. If we can successfully perform transplantations from living donors, which is a more complex procedure, then we can certainly manage cadaver transplantations," Nazaryan says.

Photo credit: Arabkir Medical Centre

She stated that the system requires significant financial, organizational, and medical efforts. Organs can only be harvested from a deceased person after brain death has been confirmed. A single doctor cannot make this confirmation; a special committee must confirm it.

Once brain death is confirmed, the doctor should inform the family members about the brain death and explain that, according to the law, all life-support devices must be turned off within 48 hours. After giving the family time to process this information, the doctor should then discuss the possibility of organ donation, explaining that if the family agrees, the deceased person could become a donor, potentially saving at least 4-5 lives.

“Doctors are concerned that people may not fully understand the need for their loved one's organs to be used for cadaver transplantation. Following the pandemic and the war, people's mental state has become unstable, and to some extent, there is mistrust of medical professionals. A family must be very well-informed to understand the importance of the moment and give consent," Nazaryan says.

Arsen Torosyan: I would be happy if my organs could help save someone's life after my passing.

Arsen Torosyan, a former Minister of Health (2018-2021) and now a member of the Parliament from the "Civil Contract" faction, strongly supports the introduction of the cadaver organ transplantation system. He notes that implementing this system was a primary goal of the Ministry. There were discussions and study trips to Moscow and Minsk, but the pandemic and subsequent war shifted the Ministry’s priorities.

Photo credit: Lena Sahakyan

"Then, I was no longer the minister. If I had stayed in office, I can't say that we would have made more progress with cadaver transplantations because history doesn't deal in 'what-ifs.' However, this program was a key part of my beliefs and political objectives, which is why it was revived with significant momentum. We are now in the second phase of that effort, and I hope we will achieve it," Torosyan reflects.

“We conducted a pilot program at Erebuni Medical Center to identify patients who could be declared brain dead, meaning there was no chance of recovery and life support should be withdrawn. The line is very delicate. The law must offer clear protection for doctors to ensure they aren't afraid of confrontation with the family of the deceased. There could also be religious sensitivities, as some sects even oppose blood transfusions. These factors need to be taken into account as well.”

Ara Babloyan, chairman of the board of directors and scientific director of the Arabkir Medical Center, a doctor and former speaker of the National Assembly, emphasizes that the law is structured in a way to minimize the risk of errors. He highlights the importance of ensuring that the committee responsible for confirming brain death remains impartial, with no ties to either the organ donor or the recipient.

"We don't just take a single organ from a cadaver donor; we harvest both kidneys, the liver, heart, and pancreas. If all these surgeries are carried out, five lives can be saved at once. In the future, we can also consider transplanting lungs and other organs," Babloyan explains.

Photo credit: Lilit Grigoryan

Ara Babloyan emphasizes the need to regulate two key processes. The first involves the medical center where brain death is confirmed. After confirming brain death, the medical center should work with the family and conduct thorough research to ensure the deceased is a suitable donor, meaning he had no diseases that could harm the recipient (transplantee). The same facility should then perform the surgery to harvest, preserve, and transport the organs to various hospitals for transplantation. Given these responsibilities, such a medical center should receive full state funding.

"Brain death should be confirmed in large hospitals for both adults and children, including those in regions," says Ara Babloyan, adding:

“The second important aspect involves establishing a fair waiting list. Currently, organ transplantations from living donors (such as liver or kidney) are partially funded by the state and partially by the patient, which excludes those without sufficient financial resources. In contrast, the waiting list for receiving an organ from a deceased donor should be determined by the patient's medical condition and compatibility with the donor, not their financial situation. Otherwise, only those who can afford it would be included, leaving out those who are economically disadvantaged. To ensure social justice, the state should fully cover the costs of organ transplantations from deceased donors.”

According to Arsen Torosyan, the organ donation system must be completely trustworthy, ensuring that the donor's family and the general public are entirely confident that all possible efforts to save the donor's life have been exhausted. He also emphasizes that the registry should be managed by an impartial body that is not affiliated with any hospital. This will ensure that no one's place on the waiting list is unfairly influenced and the system is free from potential corruption.

Helen Nazaryan explains that to prevent such issues, a person’s eligibility as a potential donor becomes visible in the system only after brain death has been officially confirmed.

"The doctor should not be aware of the potential for organ donation while treating the patient. The focus must remain on saving the patient's life. Only after brain death is confirmed the doctor can access information about whether the patient is registered as a donor," Nazaryan explains.

The organ donation registry will use a scoring system to prioritize transplant recipients based on their urgency. Factors such as age, the urgency of the transplantation, compatibility with potential donors, and required financial contributions will be included in the form.

Arsen Torosyan highlights the need for rapid organ transportation, such as helicopters, to transport organs from remote locations like Meghri to Yerevan. For successful transplantation, the organs must be both healthy and compatible with the recipient. Traumatic deaths, especially those caused by car accidents, can be particularly relevant for donation.

"Financial arrangements need to be clearly defined. For planned surgeries, patients are aware of the costs and can secure the necessary funds. However, in the case of organ donations, an organ can become available at any moment, and the state cannot expect patients to quickly gather money for a transplant from someone who died in an accident. Additionally, after the transplantation, patients will require ongoing monitoring and medication, which should be covered by the state," Torosyan says.

Torosyan believes it’s time to have an open public conversation about organ donation from deceased individuals. He emphasizes that the information should be presented carefully to avoid causing widespread opposition.

"I can already foresee the criticisms: being labeled as Soros-funded, Armenian gene, or accusations of selling our children's organs. But we must continue to explain everything clearly and transparently. This isn't about death; it's about life. I would be glad if my organs could save someone after my death. Once I'm gone, why not help someone else? The value of life on Earth should take precedence over concerns about the afterlife," says the member of the National Assembly.

Ara Babloyan notes that the number of citizens needing dialysis and surgery increases more rapidly each year compared to the number of surgeries actually performed. He adds that kidney transplantations in Armenia would be significantly higher if cadaver organ donation was implemented.

"The delay is primarily due to psychological barriers: unfortunately, society is not yet ready to accept the idea of organ donation from deceased individuals. There is a need to engage with the public in every possible way to raise awareness and help people understand the essence of this issue. Public awareness should be raised to a level similar to that of blood donation, where many people willingly respond to calls for blood donors. If a similar attitude is developed towards organ donation from cadaver donors, it could save the lives of many people in need of heart, liver, kidney, pancreas, and other organ transplants," Ara Babloyan says.

He believes that trying to preserve the life of a brain-dead person is futile and an "unnecessary expense," as brain death is irreversible and equivalent to biological death. “Once brain death is confirmed, the person is considered dead. Continuing to use state funds and financial contributions from relatives for their care is not justified.”

The doctor believes that the primary focus of healthcare funding should be on saving lives. If that is no longer possible, resources should then be redirected to maintain the individual as a cadaver donor. Since healthcare funding comes from taxpayers, it should be used to save lives.

"In many countries, when applying for a driver's license, people sign a document indicating whether they agree to become an organ donor after death. We implemented this practice for a while, but while around 85% of people in European countries consent, not a single person in our country has agreed," Babloyan says.

Araik Voskanyan noted that before the 44-day war, efforts were made to establish a cadaver transplantation system at the Astghik and Arabkir medical centers. However, these efforts were halted after the war and have not yet been resumed.

Photo credit: Gohar Sargsyan

"No one has been in contact with us (from the Ministry of Health - ed..). I'm not sure if the interruption was due to the change of ministers, but the timing suggests it might be. Whether we like it or not, we must introduce cadaver transplantation in Armenia. It's a common practice in most countries, and we can't isolate ourselves," Voskanyan says.

Voskanyan thinks that the church can help accelerate the process. "I heard that in Iran, the spiritual leader declared that those who become organ donors after death will be granted entry to heaven. This encourages believers," he says.

Rev. Fr. Yesayi Artenyan, head of the Information Service Department at the Mother See, states that the Armenian Apostolic Church supports cadaver transplantation as long as it is free from any murky deals and trafficking.

"We believe that a person might miraculously recover from a critical condition, and if there is no other way to save his life, we have no objections. However, it is important to ensure that it doesn't become a business. Experts should clearly explain the process and address any concern," says the clergyman.

After the introduction of cadaver transplantation, it will be possible to carry out heart transplantation in Armenia.

“We are technically and professionally equipped to carry out heart transplantations if cadaver transplantations are implemented”, Araik Voskanyan emphasizes.

Arsen Torosyan finds it difficult to estimate the total cost of implementing the cadaver organ donation system. A one-time expense of at least 50 million AMD will be needed for the registry, which can be adapted from an existing system. Additional costs include training programs requiring the involvement of international experts. Beyond the standard costs for liver and kidney transplantations, there will be extra expenses for organ preservation. Torosyan also notes that the devices needed for transporting the organs will be relatively affordable, costing around 20-38 million AMD.

"Initially, I am confident that Armenia can secure the funding needed for the first surgery; it’s entirely possible. Scaling the system, however, will take time, likely around five years for full implementation. Budget allocation will be necessary, for instance, planning for five cadaver transplantations in a given year. However, once the system is operational, it might not meet the demand, which could lead to public frustration. We need to be prepared for that as well. I firmly believe that with political commitment, we can achieve this. We’ve been, and still are, working toward it, though progress may be a bit slow," Arsen Torosyan emphasizes.

Over 3.6 million AMD annually for each dialysis patient

As of April 1, 2024, 1,306 patients are undergoing hemodialysis under the state program, and around 740 of them are in need of a kidney transplant.

The Ministry of Health allocates over 3 million AMD annually for each dialysis patient. This covers approximately 156 dialysis sessions, costing 22,000 AMD per session under the state program, and 84 vials of erythropoietin beta/Recarmon, priced at 226,800 AMD.

By implementing cadaver transplantation, the government could potentially save approximately 266 million AMD annually by transplanting 740 patients. This saving could be redirected to making cadaver transplantations accessible. Furthermore, each successful kidney transplantation would reduce the number of patients needing dialysis, leading to further cost reductions for the Ministry of Health.

Currently, despite high demand, liver and kidney surgeries rarely exceed a dozen per year. Although exact statistics on the number of deaths due to the lack of donors are not available, it is clear that if the 2002 law had been implemented, many lives could have been saved over the past 22 years.

Main photo credit: Artsvik Davtyan

This investigation was conducted within "Student Journalism Investigations" project by "Investigative Journalists" NGO with the support of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom South Caucasus Yerevan Office.

The views and opinions expressed in this investigation do not necessary reflect the position of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom and its employees.

Authors

Students

Lilit

Grigoryan

Students

Lena

Sahakyan

Students

Gohar Sargsyan

Instructors

Instructors

Sargis

Kharazyan

Instructors

Tirayr

Muradyan

Instructors

Edik

Baghdasaryan

Instructors

Mariam

Barseghyan

Team

Team

Harutyun

Mansuryan

Team

Lilit

Tarkhanyan