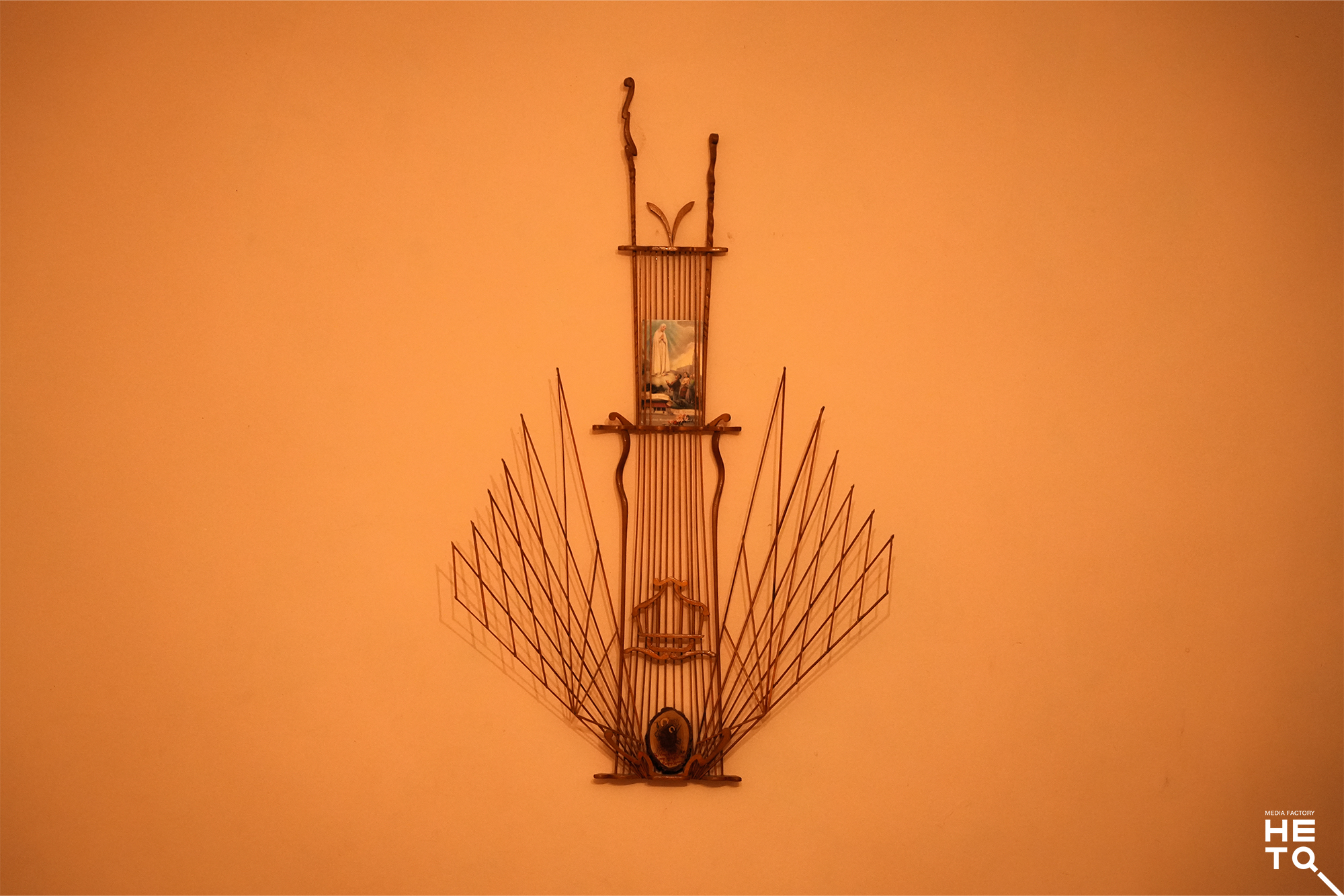

While moving from the far north of Armenia to the far south, Samvel’s handcrafted gift for Arusyak was broken.

You are the light, I am the eye.

Without light, the eye is dark.

You are the water, I, the fish.

Without water the fish will die.Throw back the fish in a new stream,

somehow it lives, fights to survive.

But if we are parted, you and I,

death is less evil. I’d choose to die.(Translated by Diana Der-Hovanessian, 1984, New York)

The gift-stone was engraved with verses by Nahapet Kuchak, along with a carved pomegranate tree below. Samvel and Arusyak did not keep the broken gift.

In 1986, four families from the village of Amasia in Shirak Region decided to relocate to Vahravar in Syunik. They had read a notice in the “Sovetakan Hayastan” (Soviet Armenia) daily newspaper about resettling in rural areas, with promises of a house and a job for those moving to remote villages. Samvel Ivanyan, who had only read about village life in books, was eager to experience it firsthand and felt inspired by the idea of reviving the village. He arrived in Vahravar with his wife and two children. At the time, Vahravar was home to around 40-50 families, offering a kindergarten and primary school. Today, the village has 22 registered residents.

Initially, Samvel and his family stayed in temporary housing before moving into one of the four houses built for newcomers to the village. The locals were primarily engaged in animal husbandry, and the family was given ten lambs. Over the following years, he expanded his herd from ten to twenty, then forty. Samvel had goats for many years until his health began to decline. However, when his sons moved to the city, and no one was left to help him, Samvel gave up animal husbandry. He now cultivates pomegranate, fig, walnut trees, and berry bushes, which provide for his family.

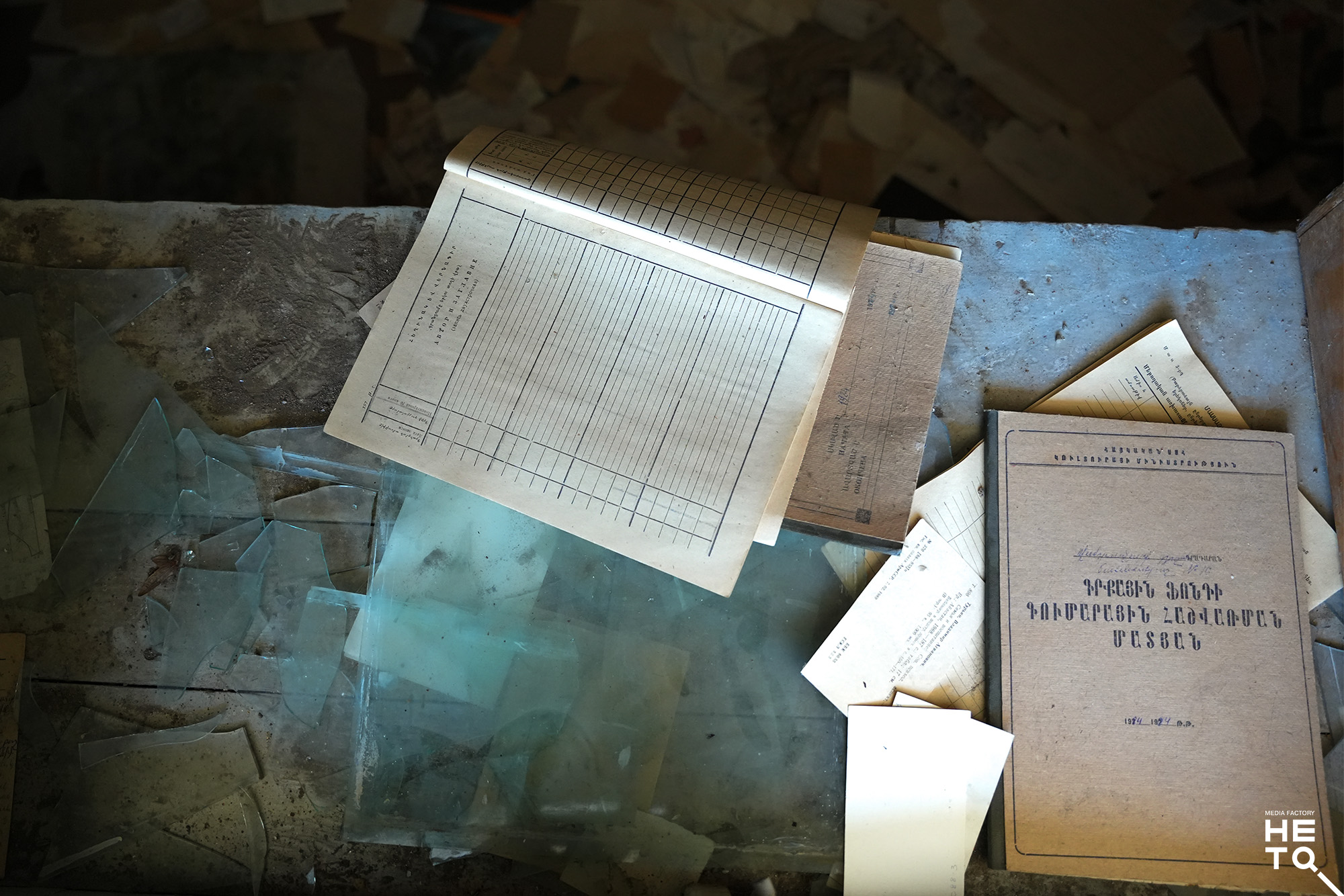

Samvel graduated from the Gyumri School of Fine Arts, named after Panos Terlemezian, and is a professional designer. Before moving to Syunik, he worked at the Amasia library and the "Arpi" cinema theater, creating movie advertisements and designing book covers. After settling in Vahravar, he worked part-time as an accountant for the village administration, spending the rest of his day arable farming and woodworking.

"When we first arrived in Vahravar, I couldn’t tell a plum tree from a fig tree," Samvel says. “But I quickly immersed myself in nature, setting aside my paintbrush. I began creating in new ways, discovering nature, and becoming more connected to it.”

Samvel’s wife, Arusyak, is a teacher. After they moved to Vahravar, she began working at the village primary school, which had only six students at the time.

Some locals viewed the newcomers unfavorably, as they themselves lacked jobs while the newcomers received both housing and employment from the state. Eventually, Samvel’s friends returned to Amasia with their families, and after living in the village for two years, Samvel and Arusyak also considered leaving Vahravar. They had decided to move, but circumstances prevented it. Samvel wonders what might have happened if they had managed to return to Amasia before the devastating earthquake of 1988, which destroyed their house there. As a result, they were forced to stay in Vahravar.

The First Nagorno-Karabakh War and the hardships of the post-Soviet period led many people to leave Vahravar. In 1999, the village school closed its doors, and Arusyak moved with the last five students to the nearby Lehvaz school, where she continues to work to this day. Lehvaz is 4 km from Vahravar. For part of the year, Arusyak uses public transport to get to school, but from November to May, she takes a taxi at her own expense.

"In the summer, the village is crowded, but in the winter, people move to the city. Only a few stay in these three villages—Vahravar, Kuris, and Gudemnis—and public transport is suspended during these months. If we are few, does that mean we should die? The transport should be available even for just one person, right? Am I at fault because my home is here? How am I supposed to go to school and back?" Arusyak expresses her frustration.

The village faces many problems, including road, transportation, gas, and water issues.

"The village's main problem is the water supply. The pipes are directly connected to the river, so when the river gets cloudy, the muddy water enters our houses. We have to place filters in five different spots to be able to use the water," says Arusyak.

The village also has a natural gas problem: there is no gas supply. The gas pipes running to Meghri pass by Vahravar, and during construction, the municipality promised that Vahravar would be connected to gas, but they never followed through. For the past 14 years, the couple has had to spend the winter in Meghri at their son's house, only returning to Vahravar to celebrate the New Year with the whole family.

Vahravar has 44 houses, but only five are inhabited in winter. According to the former village head, Sargis Arakelyan, the Vahravar functions as a summer village, with up to 70 people residing there in the warmer months. Most of the villagers engage in animal husbandry and rely on fall harvests of fruits and vegetables, which they sell in Meghri.

There is a dilapidated church in Vahravar, and people rarely visit it. The stones have shifted, and the cracks have widened, causing concern that it may collapse.

"After the 2020 war, we bought a house in Yerevan last year because there were rumors that Meghri might be taken for a corridor. We have four grandchildren, so we took them to Yerevan, to a relative’s house, where they stayed for about a month until that situation calmed down. Not knowing where to take the children or how to care for them was incredibly stressful. We even had to sell some possessions to buy a house in Yerevan, just in case—God forbid anything happens- we would at least have a place to stay. Otherwise, where would we take our children?" Arusyak says.

After starting their own families, Samvel and Arusyak's sons moved from Vahravar to Meghri. Although there isn't much for young families in the village, they have maintained their connection to it. Samvel's grandson, Aram, picked up his grandfather’s craft. When he wants to get away from the city in his free days, he visits the village to work with his grandfather on woodworking and painting. His grandfather taught him drawing, while Aram has developed his painting skills on his own.

Aram hasn't yet decided on his future career—whether he wants to be an architect, engineer, or designer. He has many ideas, including plans to build a three-story house in the capital with a cinema and a game room. He believes pursuing such a project in the village is pointless due to the lack of space and people.

Aram visits the village more frequently than his siblings. He finds Vahravar interesting and enjoys exploring its abandoned buildings.

The last attempt to resettle Vahravar was made during the Soviet era, but the collapse of the USSR left the project incomplete. The current development plan for the expanded Meghri community doesn't include Vahravar. Despite this, the Government still considers the village a privileged settlement and offers 5 million AMD to Artsakh residents to purchase a house there. However, no residents from Artsakh have moved to Vahravar.

Samvel and Arusyak can't imagine their lives without Vahravar and are saddened by the fact that people are leaving the village.

"After 4 or 5 years, these last Mohicans will eventually leave, and no one in this village will open his doors during the winter. Isn't it a pity to leave behind this beauty, such a miracle, such nature? Who will take care of all this? Why should we leave? Where would we go?" says Arusyak.

— “When you grow up, will you come to the village?” I ask Aram.

— I don't know.

This project was supported by CFLI. The views expressed in this video are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of CFLI.

Author

Students

Lilit

Margaryan

Instructor

Instructors

Mariam

Barseghyan

Team

Team

Harutyun

Mansuryan

Team

Zhanna

Bekiryan

Team

Anush

Mkrtchyan

Team

Lilit

Tarkhanyan